Western media uses the Iran–Israel war to justify regime change under the banner of democracy.

This brief clarifies Iran’s political system beyond propaganda.

Iran combines democratic elements (elected president and parliament) with strong theocratic authority (Supreme Leader and Guardian Council).

Western democracies also rely on unelected bodies with major influence (e.g., Constitutional Council in France, Supreme Court in the U.S.).

Theocracy isn’t inherently anti-democratic if it’s based on popular consent.

The real debate isn’t democracy vs. dictatorship — it’s who holds lasting power and how that power is legitimized.

Since the beginning of the 12-day war between Iran and Israel, a large-scale neoconservative media offensive has invaded our screens.

In the name of "democracy," many Western journalists, columnists, and politicians have legitimized the Israeli attack not to put an end to the Iranian nuclear program, which is unattainable given the depth of the facilities where the enrichment centrifuges are located, but for yet another regime change in the Middle East led by a Western ally.

We are not here to determine whether democracy and the values of the Enlightenment that emerged during the French Revolution over 200 years ago are the best possible system of governance, and even less whether it should be imposed on Iran by foreign powers as the West has repeatedly tried in Iraq, Syria, or Libya with the consequences that followed.

In this IB, the primary goal is to clarify the political situation in Iran by dusting off the propaganda of the Iranian regime loyalists and that of its detractors at a time when we hear everything and anything about the current political situation in Iran.

On December 3, 1979, just a few months after the departure of the last Shah of Iran from the Pahlavi dynasty, 71% of eligible Iranians went to the polls to approve the new constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran by 99.5%.

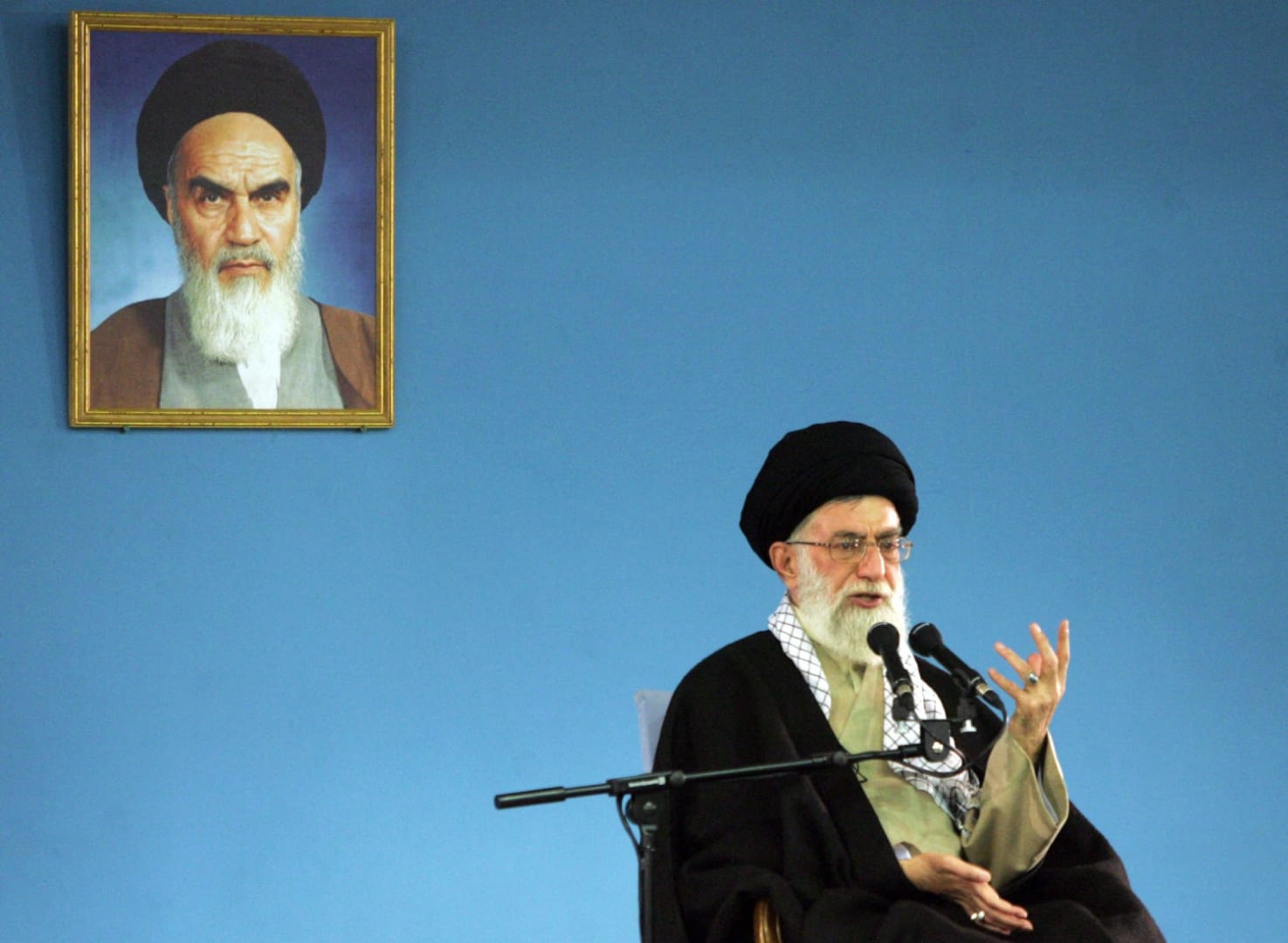

This constitution laid the foundations for a hybrid system inspired both by certain Western democracies with a unicameral system, with the Majlis whose deputies are elected by direct universal suffrage for 4 years, but also Islamic, similar to the functioning of certain caliphates throughout history, with a Supreme Leader theoretically chosen for life by the Assembly of Experts, who are nothing more than Islamic jurists themselves elected by direct universal suffrage every 8 years.

The Supreme Leader is primarily a religious figure of Shia Islam, which is the dominant Islamic branch in Iran but also in Iraq, with many followers in Lebanon and Syria. He is also the head of the armed forces, in addition to being the keeper of the seals and at the head of the state media.

Moreover, the President of the Republic, elected for a 4-year term by direct universal suffrage, is a public figure before being a political symbol; he represents the Supreme Leader through his interventions both within the country and abroad. The constitution limits his responsibilities, which largely confer the executive apparatus to the Supreme Leader.

The main counter-power to the Majlis (parliament) is the Guardian Council, which meticulously analyzes each proposed law and either approves or rejects it based on the constitution. The council is composed of 12 members, 6 chosen by the Majlis and the other 6 by the Supreme Leader.

The considerable influence of the Guardian Council of the Constitution over the fate of any passed law could be considered a blatant violation of the principle of democracy due to the non-electoral nature of the selection of half of its members, but when focusing on the current situation in other countries that fully claim to be democratic, the reality is similar.

In France, any bill, after being approved by the National Assembly and the Senate, can be approved or rejected by the Constitutional Council, whose 9 members are not elected but chosen by the President of the Republic, the President of the National Assembly, and the President of the Senate for a non-renewable term of 9 years. Thus, a newly elected majority may encounter a Constitutional Council whose members reflect the convictions of a former majority.

On the other side of the Atlantic, the American president appoints Supreme Court members for life, thus giving the Republican or Democratic party a considerable advantage over the legislative effectiveness or lack thereof of future administrations. One can note the example of Donald Trump, who had the "chance" to serve a term during which 2 judges died and one retired, allowing President Trump to appoint 3 Republican judges for life, thus granting an immense advantage to the Republicans. The effects were felt as early as Joe Biden's term with the overturning of the Roe v. Wade decision, which recognized women's constitutional right to abortion in the United States, deeming this decision unconstitutional, even though the president, the Senate, and the House of Representatives were in the hands of the Democrats, who are naturally pro-abortion and whose members are elected democratically.

These examples show us that popular sovereignty is merely a fantasy that has never actually come to fruition in the West; the complexity of applying direct democracy on a large scale forces every country to entrust certain appointments of high-ranking decision-making officials to elected representatives, whose choices have consequences far beyond their own mandate.

Moreover, Iran is criticized for its theocratic nature, on the grounds that its Constitution is based on Islam. But a theocracy is not necessarily anti-democratic. If the people freely adhere to a religious constitutional basis and accept that this basis is fixed, then it does not contradict democratic principles. Democracy does not necessarily imply the constant change of laws or values. It is primarily based on popular adherence to the existing system.